BBC/Gary Fletcher

BBC/Gary FletcherSomeone moved the UK’s oldest satellite and there seems to be no clue as to exactly who, when or why.

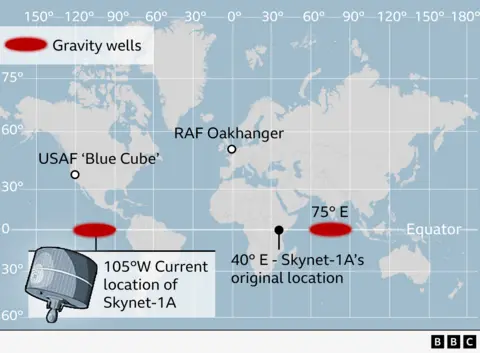

Launched in 1969, just months after humans first set foot on the moon, Skynet-1A was placed high above the east coast of Africa to relay communications to British forces.

When the spacecraft stopped working a few years later, gravity could be expected to pull it even further east, over the Indian Ocean.

But today, amazingly, Skynet-1A is actually half a planet away, in a position 22,369 miles (36,000 km) above America.

Orbital mechanics mean it’s unlikely the half-ton military spacecraft will simply drift to its current location.

Almost certainly, she was ordered to fire her thrusters in the mid-1970s to take her west. The question is who was he and with what authority and purpose?

It is intriguing that key information about a once vital national security asset could disappear. But glamor aside, you might reasonably ask why it still matters. After all, we’re talking about some space junk dumped from 50 years ago.

“It’s still important because whoever moved Skynet-1A did us a bit of a favour,” says space consultant Dr Stuart Eves.

“It’s now in what we call a ‘gravity well’ at 105 degrees west longitude, bobbing back and forth like a marble at the bottom of a bowl. And unfortunately that brings it close to other satellite traffic on a regular basis.

“Because it’s dead, the risk is that it could collide with something, and because it’s ‘our’ satellite we’re still responsible for it,” he explains.

BBC/Gary Fletcher

BBC/Gary FletcherDr Eves has scoured old satellite catalogues, the National Archives and spoken to satellite experts around the world, but he can find no record of the end-of-life behavior of Britain’s oldest ship.

It can be tempting to reach for a conspiracy theory or two, not least because it’s hard to hear the name “Skynet” without thinking of the malevolent and self-aware artificial intelligence (AI) system in The Terminator film franchise.

But there is no connection other than the name and, in any case, real life is always more prosaic.

What we do know is that Skynet-1A was manufactured in the US by the now-defunct Philco Ford aerospace company and was put into space by a US Air Force Delta rocket.

“The first Skynet satellite revolutionized UK telecommunications capacity, allowing London to securely communicate with British forces as far away as Singapore. Technologically, however, Skynet-1A was more American than British, as the United States The United States built it and released it.” observed Dr Aaron Bateman in a recent paper on the history of the Skynet program, which is now in its fifth generation.

This view is confirmed by Graham Davison who flew Skynet-1A in the early 70s from its UK operations center at RAF Oakhanger in Hampshire.

“The Americans initially controlled the satellite in orbit. They tested all our software against theirs, before eventually passing control to the RAF,” the long-retired engineer told me.

“Essentially, there was dual control, but when or why Skynet-1A might have been handed back to the Americans, which seems likely – I’m afraid I can’t remember,” says Mr Davison, who is now at the 80s. .

Sunnyvale Heritage Park Museum

Sunnyvale Heritage Park MuseumRachel Hill, a PhD student from University College London, has also searched the National Archives.

Her readings have led her to a very reasonable possibility.

“A Skynet team from Oakhanger would go to the USAF satellite facility in Sunnyvale (colloquially known as the Blue Cube) and operate Skynet during the ‘Oakout’. This is when control was temporarily transferred to the US while Oakhanger was down for essential maintenance. Maybe the move could have happened then?” Mrs. Hill speculated.

Official, though incomplete, records of Skynet-1A’s status suggest that final command was left in American hands when Oakhanger lost sight of the satellite in June 1977.

But however Skynet-1A was then moved to its current position, it was ultimately allowed to die in a difficult place when it really should have been placed in an “orbital graveyard”.

This refers to an even higher region in the sky where old space debris is not in danger of colliding with active telecommunications satellites.

Cemeteries are now standard practice, but in the 1970s no one thought much about the sustainability of the space.

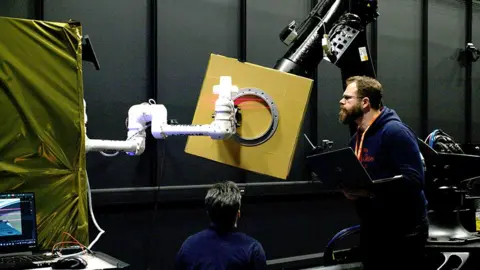

Astroscale

AstroscaleSince then, attitudes have changed because the space field is becoming overcrowded.

At 105 degrees west longitude, an active satellite can see a piece of debris come within 50 km of its position up to four times a day.

That might sound like they’re nowhere near each other, but at the speed these helpless objects are moving, it’s starting to get a little too close for comfort.

The MoD said Skynet-1A was continuously monitored by the UK’s National Space Operations Centre. Other satellite operators are informed if a particularly close connection is likely, in case they have to take evasive action.

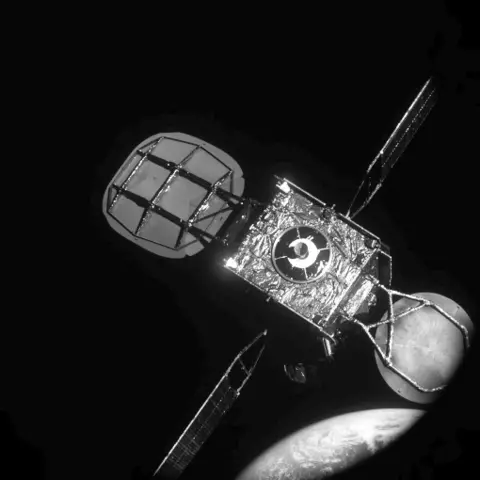

Northrop Grumman

Northrop GrummanUltimately, however, the British government may have to consider removing the old satellite to a safer location.

Technologies are being developed to capture debris left in space.

Already, the United Kingdom’s Space Agency is funding efforts to do this at lower altitudes, and the Americans and Chinese have shown that it’s possible to trap antiquated hardware even in the kind of high orbit occupied by Skynet— 1A.

“Some space debris is like a ticking time bomb,” observed Moriba Jah, a professor of aerospace engineering at the University of Texas at Austin.

“We have to avoid what I call super-dispersion events. When these things explode or something collides with them, it generates thousands of pieces of debris that then become a hazard to something else that we care about.”